Installation picture from Yuri Shimojo's solo exhibition, Mirrors, on view at Praise Shadows Art Gallery in December 2024. Photo by Dan Watkins Photography.

Place, Material, and the Mirrored Self: How Three Innovative Ink Makers Helped Bring “Mirrors” by Yuri Shimojo to Life

An artist with more than fifty years of experience in painting, drawing, and illustration, Yuri Shimojo encompasses all the radiant contradictions of her extraordinary life. The Tokyo-raised, NYC/Kyoto-based artist will, quite regularly, break the upright posture inherited from centuries of samurai ancestry to let out an irreverent snort or a colorful curse no doubt picked up from her years partying with some of the most important scene-makers in the US and Japan. She will pause in the midst of a particularly silly floor-rolling giggle to serve you exquisitely prepared tea. Her inner child—little Yuri—is perpetually present. And so too is the artist, an exacting master who perceives both in moments and in eons to channel all the lives we live—the before, the now, the after—into haunting and meditative ink works.

Having survived the loss of her entire family by the age of twenty-nine, Shimojo seems to adopt a new one wherever she goes, enlisting creators, scientists, musicians, and thinkers in a shared pursuit of artmaking and art living. Her current show at Praise Shadows Art Gallery, Mirrors, is the result of such collaborations, from the scroll master who mounted the works in Osaka to three ink mavericks—artist, researcher and ochre specialist Heidi Gustafson, founder of Toronto Ink Company Jason Logan, and Thomas Little, an artist who creates inks derived from dissolved guns. Each of these creators concocted inks and/or pigments especially for Shimojo from materials as disparate as volcanic ash, mica, blood, and guns. Here, I talk to them about their own methods of making, the myriad definitions of place and perspective, and how—in her constant pursuit of rendering truth—Shimojo has conjured this new series. Full of wandering unbroken lines and fantastical mirrors, she has created pieces that reflect us all by etching marks that are indelibly her own.

The following has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Jessica Shearer: I thought we could organize this conversation around the principles that are evident in this body of work: a real deep sense of place, histories (material, ancestral), and how art making relates to your own personal understanding of self. Let’s begin with place—I really want to start with you Thomas, because in researching this piece I found you have a very specific requirement—you have to live near, is it deep water?

Thomas Little: It's dark water. Specifically dark water. Right now it's behind me. Dark waters are tannic rich waterways here on the eastern part of North Carolina and on the East coast. They're beautiful black tributaries and I grew up swimming in them and playing in them, so that's very much part of my place.

Heidi Gustafson: I've been thinking about the relationship of place and point of view—and questioning how we define what place is and no-place is. There's something powerful about how you can tell you're in a place if you can shift your point of view to experience yourself as the place. You could even say a tree is a place, if you were able to enter into the point of view of a tree. I could say that I am a place, if I enter the point of view of myself, you could say the dark river is a place if you enter the point of view of the whole river, or the no place is a place if you can enter the point of view of it. That's an organismic way of thinking about place—that place can be animated by having a point of view. And once you do that, then you can start. It doesn't really matter if it's geologic or spiritual or written. And that’s the question I’m thinking about—what is at stake when we use the word place?

Jason Logan: And then cross-referencing that with Indigenous forms of language where place isn't necessarily a name on a map. You might not have the name of a lake, you might just have a relation to that lake under certain conditions or a little piece of that lake. There’s also just the western tradition of place: power, mapping, boundaries, putting words to things that maybe were better without words. To Heidi's point, if a part of a place is a being, then it's talking back to you and it is not necessarily up to us to name it and be inside it. It brings to mind many of the Indigenous languages of Canada, where there are ways of relating to the ground and the water and the stuff that people walk on where it's not about subject and object. It's inter-relational and it happens at the level of language.

TL: Yeah, place is just a concept that you can shift in your mind. We are moving on a rock that's flying through space all the time; we're never in the same spot, even when we sit still.

JS: Given how elusive place can be, let’s think about one’s responsiveness to material. Thomas, your ink is almost exclusively made with guns, and Heidi, you're working with ochers and earth pigments, and then Jason, you'll work with so many things. What does it feel like to engage in the search for material?

Artist Heidi Gustafson sources and saves ochres from around the world, having developed a working archive of more than 600 pigments. Photo by Erik Dinnel. Courtesy of the artist.

HG: Something I love about all of our work—Yuri’s included—is that our relationship to material defines how we carry place with us, or even how we feel displaced. A lot of our work happens when we decide to take a piece of place with us. And then when do we decide it's no longer place? Once it's been processed into some other kind of energy? Or is it a color? Or is it a memory? The transformation of place into creative power is something we all grapple with.

TL: Heidi is a go-to inspiration for me a lot of times. And I think a lot about when you, Heidi, describe how everything's dirt and how art is dirt you put up on a wall that's made out of more dirt that'll eventually fall down and become dirt again. What I do with my work with guns is transitioning the object into place, which eventually will be dirt, but first it's going to be art for a little while. It’s that essential point A to point B; gun: cold iron, back to earth: warm iron. But in the meantime, it could be examined and seen before it becomes whatever place it binds or swirls into.

A drawer of gun-derived pigments made by artist Thomas Little. Photo courtesy of the artist.

JS: That’s so beautiful. And you Jason, when you're heading out to gather materials, how are you thinking about your relationship to place?

JL: My straight-ahead practice is that while I can make ink from anything, I like to make ink from things that are right at my feet. It’s not about going to exotic locales and making weird colors. It's finding things that are really, really close to me. And I find if I just look and feel in a really, really open way that the materials start speaking to me and I'm able to work with them. But the question of place and material is hard because part of my understanding about that fine line between spirit and matter is how I see it through the network of Heidi and Thomas and Yuri and a few other people.

Artist and founder of Toronto Ink Company Jason Logan makes inks from materials he forages in urban environments, the natural world, and everything in between. Photo by Lauren Kolyn. Courtesy of the artist.

JS: That sense of connection is clearly so important to all of you. I’m interested in your feelings about how the thing that you make—ink— goes to somebody else and lives in their own artistic practice. What does it mean to you to have a component for your work to be a component in somebody else's creative output?

TL: Anyone can use my ink however they want. My process is more focused on consuming the material. I want to take these guns and do the magical heavy lifting. And if someone wants to take that object and then elevate it further and make something beautiful out of it, I'm all for that. But at the same time, I don't mind pouring it down the sink. I don't mind it turning back into whatever it was or wants to be or was going to be somewhere else.

JL: But I feel like the package that you made for Yuri was somehow a whole other creature. That you have your practice as a midwife for materials—moving them along. But also you have this practice as a shrine maker or something.

HG: I definitely feel like more and more my practice is becoming akin to that of an undertaker. Most of the times that I make work or pigments for other people, the dead are involved. And that can be their own future dying. People who are dying request certain kinds of pigments. And it's not really about the use in artistic practice per se, but in the soul practice or the spirit practice of being on the earth or leaving the earth. And with Yuri, we were really honing in on her felt sense of the burden of being ancestrally tied to the earth. And I was asking: what does the portal look like for you, Yuri? When you have to leave the earth, do you want to go deeper into it? Do you want to go way out in the cosmos? But one can consider the material practice as being an organ of digestion for people's relationship to the dead, and that is the artwork, right?

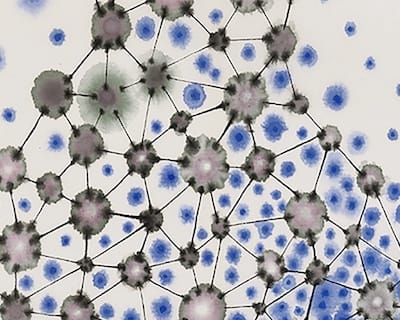

Detail of Yuri Shimojo's painting Mirror 2 (Unbroken Line: Phantom). Made from pigment derived from prehistoric volcanic dust, handmade ink from mica, sumi ink, and Japanese watercolors on washi Japanese paper (Kozo Kurotani Gasenshi).

JS: I know when the two of you were discussing where the earth pigments should come from, she originally felt like it should be from her ancestral lands in Japan, but it never felt right to her to actually dig up that earth, and then you offered something that was made from a volcanic ash was originally from Hawaii, which is a land she has so much love for. And so now the ink is so much more akin to who she feels she really is and so much less to do with where she comes from. That's beautiful.

Jason, can we talk a bit about the inks you made for Yuri? I’m especially intrigued by the one that shifts in color.

JL: The fog gray. Yeah. Yuri originally asked me for pink ink. She'd been working on cherry blossoms. So I thought okay, what could I do with blossoms? And I sent a bunch of stuff, and was kind of amazed that she immediately responded with: “I love them, but they’re not right yet.” So then it was a sort of blue, and then it was actually blue with blood, and then it was something else. I loved that someone who is always generous and gentle also just refuses to stop. Out of all the collaborations I've had, I’ve never come up against someone who has asked me to go further and keep going. It feels like a real back and forth dance between the things she doesn't know she's looking for and the thing that I didn't know I knew how to make. So some of those amazing inks that you've seen, like the fog gray, are a true collaboration.

Detail of Yuri Shimojo's painting Indra's Net. Made using 'fog gray' ink by Jason Logan.

HG: I think the way that Yuri’s practice is—and the way all of our collaborations with her are—really allows for this oracular emergence. We don't necessarily know what the intention behind the ink, or in my case, dust that we're making for Yuri is about, and we discover that together. Just yesterday, I was reading about nose breathing and the book was talking about samurai, how in the samurai tradition they would put feathers underneath their noses and they'd breathe in and breathe out, and they were appropriately practiced if they didn't move the feather at all. And then I realized that some of what I made for Yuri was the exhalation of the volcano. I'm just now learning a little bit more about what's inside of that material for both of us.

JS: I think if Yuri was told that she had to breathe slowly, she would have the biggest exhalation she could have, right? Yuri is the volcano.

JL: Yes. There's also just the spirit of ignoring the rules and being punk and refusing the first anything.

HG: But then watch her, if you had a video in the room when she's making her work, I bet you could put a feather under her nose.

JL: This goes back to the question of who's the subject and who's the object. Just the sense of playfulness or a circular notion around agency. I hope that when the audiences are standing in front of those portal mirrors, that the mirror portals will be looking back at those people.

Installation image of Mirror 6 (Golden Oval) and Mirror 3 ( Ladybug in Fog Clouds). Photo by Dan Watkins Photography.

TL: The interstitial space between things more often than not is the force that's actually shaping both places or both things, object or place. That's what makes mirrors interesting to me; you're looking at the contours of yourself, but it's the space between those contours. A fun way to interpret the idea of the mirror is when it's not a mirror. Rather the symbol of a mirror—the mirror as oracle. Or of course the fairytale mirror who tells you who's the fairest of them all.

HG: Somehow the work avoids narcissism, which is weird because if you're creating the mirror that then looks back at you and then creates an audience, aren't you just self-defining the universe for everybody? But it doesn't do that. It’s a mystery to me how that doesn't happen in her work.

JS: There are so many connotations, including the inability to look at oneself, which is kind of what kickstarted this series for Yuri, the inability to confront the specificity of who she thought she was at the time. But also there’s the sense that there's a place of possibility there, of a reflection that it is maybe not what you expected. It’s marvelous.

Mirrors by Yuri Shimojo closes December 21, 2024 at Praise Shadows Art Gallery.

Jessica Shearer is a Boston-based art writer and critic interested in explorations of gender, dislocation, and narrative. She is a senior editor at Boston Art Review; her work has also appeared in Hyperallergic and Photograph, among other publications. Photo by Mel Taing.